Ustad Zakir Hussain and genres as a concept

there is a power to breaking genres, which are often reflections of social and political realities more than aesthetic frameworks

What is joy? Is it only for children? Is it silly for adults to be joyful given how unfair and cruel the world is? Indian adults born between the 1920s to the 60s, or at least the ones I know, are particularly stoic. An exception was Ustad Zakir Hussain, one of India’s most well-known musicians.

In December of 2024 Zakirji quietly passed away, and I was struck by his death. At first I felt unworthy to write about him. I am not a trained Hindustani artist, I know very little about tabla, and I have listened to only some of his music. How could I write about him? But also, how could I not?

Zakirji was in the air.

Growing up I did not know Paul McCartney or Frank Sinatra, but I knew Ustad Zakir Hussain like I knew M.S. Subbulakshmi and Lata Mangeshkar. He was the old world and the new; devotee of an ancient art form and genre-breaking pioneer.

Without my realizing it, Zakirji has been all around me. My older sister was his student at Stanford, I have attended concerts at Ali Akbar College of Music, where Zakirji taught, and he is now buried just twenty-eight minutes from my house.

Indian classical music can be a serious matter, but Zakirji was keen on it being a matter of joy. Let me explain. The tabla is older than human memory and its origins exist in Vedic text, the ancient scriptures of Hinduism. As with most aspects of Indian heritage, the tabla is trying to achieve a spiritual awakening, known as rasa. The process by which one arrives at rasa is not mystical, but a blend of discipline, knowledge, and presence.

Although Ustad Zakir Hussain was a technician, there was a spiritual dimension to what he did and that is the legacy I want to extend. He had a desire to experiment with Indian classical music, and each experiment tried to understand some truth about our shared humanity. It is common to say he was a bridge between the East and the West because he introduced Western audiences to sounds from India, but instead of constructing a bridge, what if he was constructing an orthogonal space for us to visit? A space in which to meditate on the meaning of music, joy, and our human capacity for interconnectedness.

duets across genres

When I listen to this jugalbandi, or duet, between a chenda team and Ustadji, I find myself drawn to the chenda because they are the sound of home. These drums are widely used in southern Karnataka and are present at religious events, parades, plays, and performances. The chenda makes me want to get up dance.

The tabla player sits on the sidelines. His instrument is not like its forceful South Indian brother, with its harsh, steady stream of beats. The tabla is rain. It can fall lightly or in giant drops, a steady patter or intermittent heavy showers.

Unlike the chenda, the tabla is not keeping tempo, it is responding to the tempo. Sometimes the left hand runs away at high speeds while the other ties the audience down with delicious, loopy sounds.

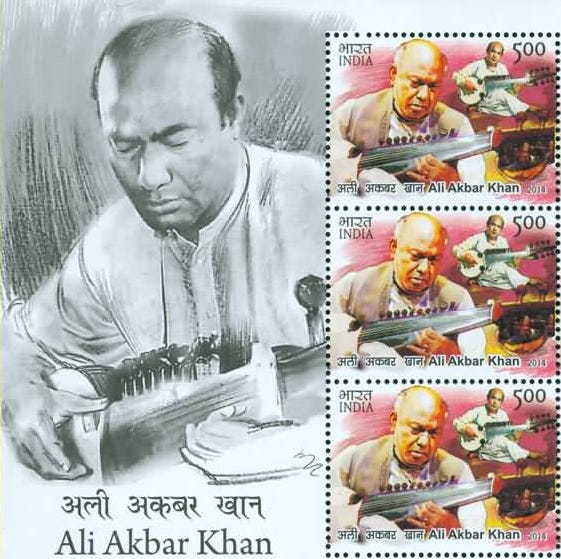

The tabla is humble, and humbler still is the devotional artist. Ustad Zakir Hussain was part of a revered musical lineage. In me is my father’s spirit, his teacher’s spirit, and his teacher’s teacher’s spirit. He learned from his father, Ustad Alla Rakha, a tabla player and accompanist to legendary Indian musicians such as Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Allaudin Khan, and Vilayat Khan.

But this undoubtedly stern group did not pass their solemnity to Zakirji. You see joy on his face as he responds to the chenda. He nods, smiles, and is fixated on the drummers. Sometimes he laughs and points at them, shakes his head as his hair flounces, and I am baffled at how they flawlessly improvise. The beats move at a blistering speed and in faultless unison, as if the musicians are all connected to one mind.

Zakirji was known for cross-genre collaboration. His father composed for the Bollywood industry and taught Zakirji; fusion was a part of him. In several interviews Zakirji expresses an openness towards all musical forms. So why this chenda-tabla duet? He might have said, why not?

My father’s father, G.T. Narayana Rao, was a music critic in Mysore as hobby. He had perfect pitch and a militant passion for Carnatic sangeeta, two qualities he hurled at unsuspecting performers. As I listen to Ustad Zakir Hussain’s experiments in fusion, I wonder if a purist like my grandfather would have found beauty in it. Given the caliber of the musicians involved I think he would have. As I have remarked in the past, if art is well-made, much is forgiven.

where three rivers meet

A duet is known as a jugalbandi but what is a trio? There is no word for it in Carnatic or Hindustani music, but there is Triveni — a place where three Indian rivers, the Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati, meet. Triveni is also the name of an Indian classical trio Zakir Hussain, Jayanthi Kumaresh, a Veena musician, and Kala Ramnath, a violinist. The trio bind so-called South Indian tradition and North Indian tradition. The binding is done by Zakirji.

As Ustadji explains, Triveni is “about honest interaction. It is where three artists come together without hesitancy or ego, and connect at a level where negativity is nowhere in sight.” The main feeling is joy.

There is a power to breaking genres, which are often reflections of social and political realities more than aesthetic frameworks. Triveni tells three aesthetic stories at once, giving a much richer perspective on humanity.

[As an artist]… if you arrive at the table with a preconceived idea… [you are] already creating an invisible fence between us… Arriving into our conversation with that open mind, that anything is possible and should be possible... but within the realm of what Indian traditional art form is. To be able to crossover… to draw upon templates that are there… this should be what one should do. [Triveni] is a simultaneous triple journey as one… [we] allow each other the space to contribute, speak one’s mind, and get [one’s] point across - Ustad Zakir Hussain

the original intention of music

In many of his conversations about Hindustani music Zakirji mentions rasa, or a feeling of wonder and oneness.

Rasa is about feeling the good, the bad, the ugly, the loving, the notable, the great, all of it in the music… [the artist] is not calculating… it is a collective effort between [the artist], the instruments, the other musicians, the audience… the collective awareness of each feeling and each emotion elevates all of us together [into] being humbled, being dust…everyone is feeling the same thing… that is rasa… - Zakirji

He often spoke of this feeling of oneness between musicians on stage. There was no air between us. We were the same nervous system. Our ability to make music means we have an ability to connect. Without this harmony, there is no music, no rasa.

storming the citadel

In an essay on T.M. Krishna I briefly touch on the elitist history of Carnatic music. Krishnaji has mastered the art form and so, with the weight of credibility, he asks — is it possible to separate a superiority complex from the art form? In 2020 I made a film pertaining to that question.

It took me a long time to realize, longer than I like to admit, that classical music is exclusive, regardless of style. I assumed every Indian-American grew up listening to Carnatic and Hindustani music, but my fiancé, and many other Indians I have met outside our family’s social circle, did not.

I still feel protective of Carnatic music. I cringe at remixes by untrained DJs who seem to want all the world’s music to fit into a Boiler room set, as if world peace hinged on their vibe curation.

Then again I have a friend who might say, but music is art and all art is innovation. It is people experimenting and building new sounds. There is no pure form. To this I say, only once the rules are mastered can they be broken in interesting ways. I am backed by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

If you practice for ten years, you may begin to please yourself, after 20 years you may become a performer and please the audience, after 30 years you may please even your guru, but you must practice for many more years before you finally become a true artist—then you may please even God. - Ustad Ali Akbar Khan

until we meet again

Around 2008 Zakirji played a concert in Portland, Oregon and our community packed a small church downtown. I sat in the rafters, on the floor. Indians are very skilled at finding places to sit when there are none. I craned my kneck to see the famous Ustad Zakir Hussain and, as he started playing, my first thought was, this is tabla? The tabla can do that? Zakirji nodded and smiled at his collaborator. Other times he scrunched his face, almost as if in pain. He was somewhere in-between here and there.

A crowd of South Indian Hindus were enraptured by a Kashmiri Muslim, in a Catholic church, in a Christian country. And the sky did not fall— in fact his vibrations might have cracked open a sky above the sky, a kind of heaven into which we can all return.

If you enjoy fusion music from India, Zakir Hussain recommended the following artists: Shankar Mahadevan, A.R. Rahman, Pandit Niladri Kumar, Anoushka Shankar, sarode musician Alam Khan, Taufiq Qureshi, Talvin Singh, and Karsh Kale.

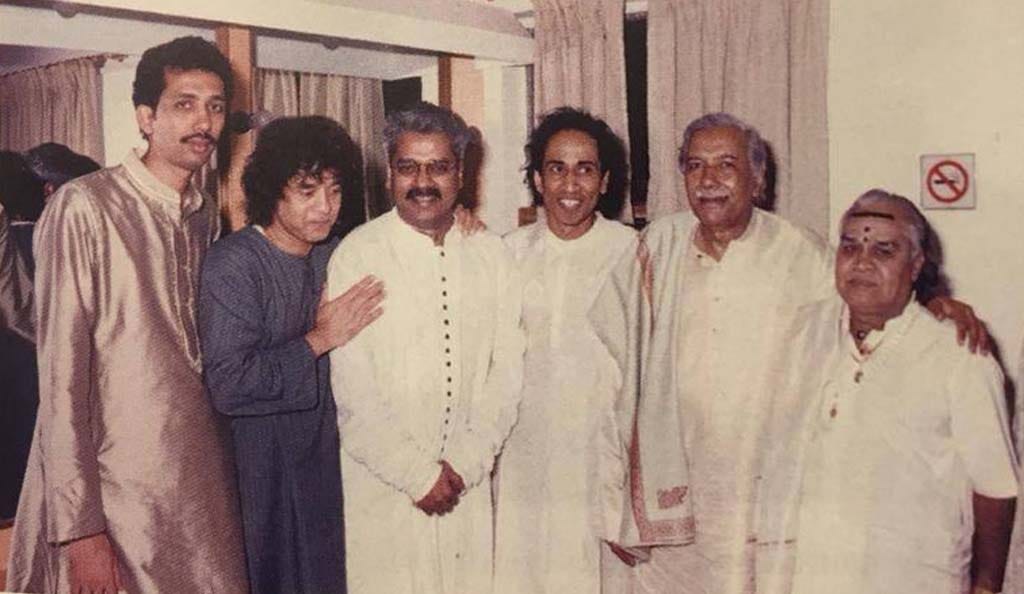

The correct sequence of names from L-R

Vikku Vinayakram, Gulam Mustafa Khan, L Shankar, Hariharan and Ustad Zakir Husain.. the last person doesn’t ring a bell